All About Obon, Japan’s Festival of Souls

- Tiffany

- Aug 11

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 16

For a few days in summer, Japan prepares for one of its most important holidays: Obon, a commemoration of deceased ancestors. Also known as “Bon,” as the “o-” in this case is an honorific prefix, it is observed in several ways, from placing offerings at the family altar to dancing the Bon Odori. As Obon draws near, read on to learn more about this time-honored summer tradition!

Obon: How It All Began

Though Obon is considered a Buddhist custom, Japan already had a tradition of ancestor worship before Buddhism was introduced to the nation, owing to its indigenous religion, Shinto. You can thus think of Obon as a blend of Shinto and Buddhist beliefs and practices.

As for the Buddhist backstory behind Obon and similar East and Southeast Asian festivals like Ghost Month, the story goes that Maha Maudgalyayana (or “Mokuren” in Japanese), one of Buddha’s most faithful disciples, discovered that his mother had become a hungry ghost, cursed to live out her afterlife suffering from insatiable hunger.

Buddha advised Mokuren to offer food to his mother and other hungry ghosts on the 15th day of the seventh month. This is a time when the gates of the afterlife are believed to open, leaving the dead free to walk the earth and visit their families.

Mokuren did as he was told, releasing his mother from her torment. The practice of making offerings to deceased loved ones soon spread, cementing the Obon tradition. It’s also said that Mokuren danced with joy upon learning that his mother was now free, inadvertently starting a new tradition in the process: the Bon Odori.

When Is Obon?

In this day and age, most of Japan observes Obon in mid-August, usually around August 13–15. However, depending on the region and which calendar you’re looking at, Obon can be observed in July, August, or even September.

The Chinese lunar calendar, which ancient Japan followed for centuries, sets the dates for Obon as the 13th to 15th of the seventh month. However, as Japan switched to the solar Gregorian calendar in 1873, there are no fixed nationwide dates for Obon.

Thus, some parts of Japan may celebrate Obon from July 13–15, as it is the seventh day of the seventh month as per the Gregorian calendar, while others might go with mid-August. Yet some others base the dates for Obon on the lunar calendar, so the dates of their Obon celebrations may vary yearly. Okinawa, for example, uses the lunar calendar's Obon dates for reference, so it usually observes Obon in September.

How Japan Traditionally Celebrates Obon

From solemn and private, to lively and large-scale, here are the ways Japan has traditionally observed Obon.

Guiding Lights: Fireworks and Lanterns

Lights play a significant role in Obon, as they are used to help spirits find their way home on mukaebon (the first day of Obon), then to guide them back to the spirit world on okuribon, the last day. This practice ranges from families hanging lanterns outside their homes, to large-scale ceremonies or festivals in parts of Japan.

For example, every year on August 16th, Kyoto sends spirits off with the ritual bonfires of Gozan no Okuribi, better known as the Daimonji Festival. On this night, large bonfires forming the shape of kanji characters, a torii shrine gate, and a boat are lit on five of Kyoto’s mountains.

Some areas hold toro nagashi (lantern-floating) festivals, in which candle-lit paper lanterns with wishes and/or messages written on them are floated down rivers. In Tokyo alone, toro nagashi events are held at Chidorigafuchi Moat in late July and the Sumida River in Asakusa in mid-August.

Similarly, Nagasaki sends spirits off with the lively Shoro Nagashi. Also known as the Spirit Boat Procession, this festival has Chinese influences owing to Nagasaki’s history of trade with China. It is a parade of “spirit boats,” some of which can be as large and elaborately decorated as a festival float, accompanied by firecrackers, gongs, and loud chants.

And, though they may seem more about wowing spectators nowadays, Japanese fireworks festivals are held in summer for a reason. Honoring the dead was one of the reasons that some of Japan’s longest-running fireworks festivals, such as the ones at Tokyo’s Sumida River and Niigata’s Nagaoka City, were held to begin with.

Offerings for the Dead

Just as Mokuren did, families leave offerings of food, as well as incense and flowers, on household altars and deceased loved ones’ graves (which they also ritually clean) during Obon.

People also decorate altars with shoryo uma (literally “spirit horse”), cucumbers and eggplants propped up on sticks. They symbolize spirits’ modes of transportation during Obon: a horse and a cow, respectively.

These animals allow spirits to reach the human world quickly while taking their time to leave, as the slender horse moves quickly, while the cow is slow—and big, which means that they also have room to carry families’ offerings back to the spirit world.

Bon Odori and Other Summer Dance Festivals

Bon Odori (“Bon dance”) refers to dances performed during Obon, traditionally meant to welcome the dead and celebrate their presence. Though various regions across Japan have their own favored styles and folk songs, Bon Odori moves are generally simple and fairly easy to learn.

Whether you believe that the deceased actually visit us during Obon, Bon dances have an undeniably communal aspect to them. At such festivals, people, usually clad in light cotton kimonos called yukata, dance around an elevated stage called a yagura from sundown until night. There may also be stalls offering refreshments, games, and/or merchandise.

As proof that traditions evolve with the times, some Bon Odori events have people dancing to rock, disco, and even anime music! If this kind of Bon Odori is your thing, the dances at Nakano, Shinjuku, and Akihabara’s Kanda Myojin Shrine—all in Tokyo—are worth checking out.

Additionally, some regions have their own distinctive Bon Odori offshoots. For example, Shikoku’s Tokushima Prefecture is the birthplace of Awa Odori, a dance style that alternates between frenetic and slow, creeping movements.

Meanwhile, neighboring Kochi Prefecture has the energetic yosakoi, characterized by its use of clappers called naruko. Though it began as a variation of the Bon Odori, yosakoi has become a very versatile dance style that can be easily combined with other music genres.

Tokushima and Kochi hold their major dance festivals around mid-August, just a few days apart from each other. But if you can’t make it all the way there, don’t worry, as Awa Odori and yosakoi have spread beyond the Shikoku region. Tokyo and other big cities across Japan have their own festivals for these dances, too!

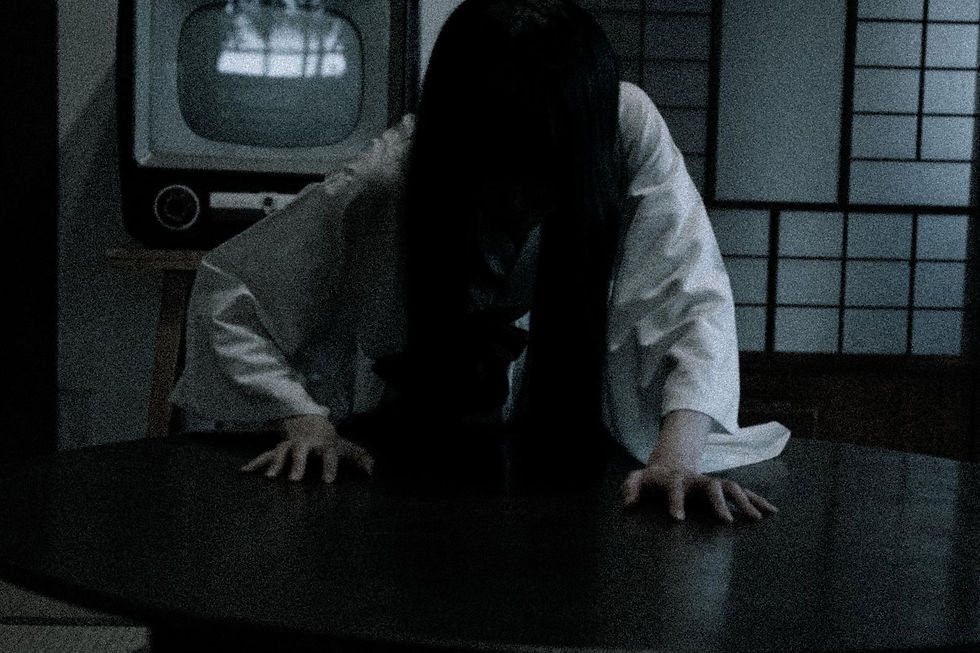

Ghost Stories for (Literal) Chills

Though Halloween may now be a big deal for young people in Japan, the country’s original spooky season has always been Obon. If you think about it, it makes sense: when the dead return to the world of the living, there will surely be some unhappy, vengeful spirits in the mix.

Scaring one another with ghost stories is both an Obon and summer tradition. Way before air conditioning existed, Japanese people believed that ghost stories would give people the chills and thus help them cool down in summer.

Japan has, since then, found more effective ways to beat the heat, but this is why, to this day, horror movies in Japan are often released in August. Also, throughout Obon, many amusement parks set up seasonal horror-themed attractions, and you may also see horror-themed TV specials and ghost-story roundups in Japanese media.

Obon in Modern-Day Japan: Is It a Public Holiday?

No, Obon is not a public holiday, though there is one that falls close to it: Mountain Day, on August 11 each year. However, many businesses across Japan will close for a few days in mid-August to give employees some time off for Obon.

During this time, many return to their hometowns for a family reunion of sorts. However, as most Japanese people nowadays are secular, only practicing certain religious and/or spiritual customs as part of their cultural traditions, they do not necessarily spend Obon in memory of their ancestors. In fact, some go vacationing during their Obon holidays!

Thus, Obon season—specifically mid-August, anywhere between August 8 to 18—is a peak time for travel in Japan. Expect higher prices for accommodation and long-distance modes of transport, crowds at airports and major train stations, congested roads and expressways, and long lines at theme parks and other popular recreational facilities.

If you’re visiting Japan around Obon, we recommend making your travel arrangements as soon as possible. Don’t wait until the last minute hoping for price drops; book whatever you can already book in advance.

And if you plan to travel via Shinkansen bullet train, it’s best to reserve seats (and luggage storage, if necessary), as lines for non-reserved seating during this time are no joke.

Get more travel tips and insights into Obon and other Japanese cultural traditions directly from a local guide! If you’re feeling shy about joining a Bon Odori, or are worried about making a faux pas at a local festival, a friendly guide who knows their stuff can surely help you out.

For sightseeing around Japan with a personal touch, consider booking a tour with TOMOGO! to connect with locals as you explore.

Feature photo by Dick Thomas Johnson / CC BY-SA 2.0

Comments